Right To Repair

Right To Repair (RTR) is a movement to convince manufacturers to build things that are repairable by third parties (individuals or independent repair companies). The claim is that manufacturers are deliberately or accidentally designing their gear to make repair difficult to impossible. This is a very passionate and complex topic, with many variables that are not obvious to most people. Because of this, there is much hyperbole on the internet around this topic.

The goal of this blog post is to discuss various issues that many people don’t consider. I will probably raise more questions than answers. But the questions are important.

Critical Thinking

Before we dive into the issues, we must discuss some critical thinking. Reading other articles and watching videos on RTR makes it clear that many people dive into conspiracy theories and other irrational thinking. We can’t have that here, so…

Hanlon’s Razor is similar to Occam’s Razor and simply states:

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

What this means for RTR is that you can’t claim that a company is intentionally doing something wrong without evidence that they are intentionally doing something wrong. In some cases, there is evidence so we don’t need to make stuff up too.

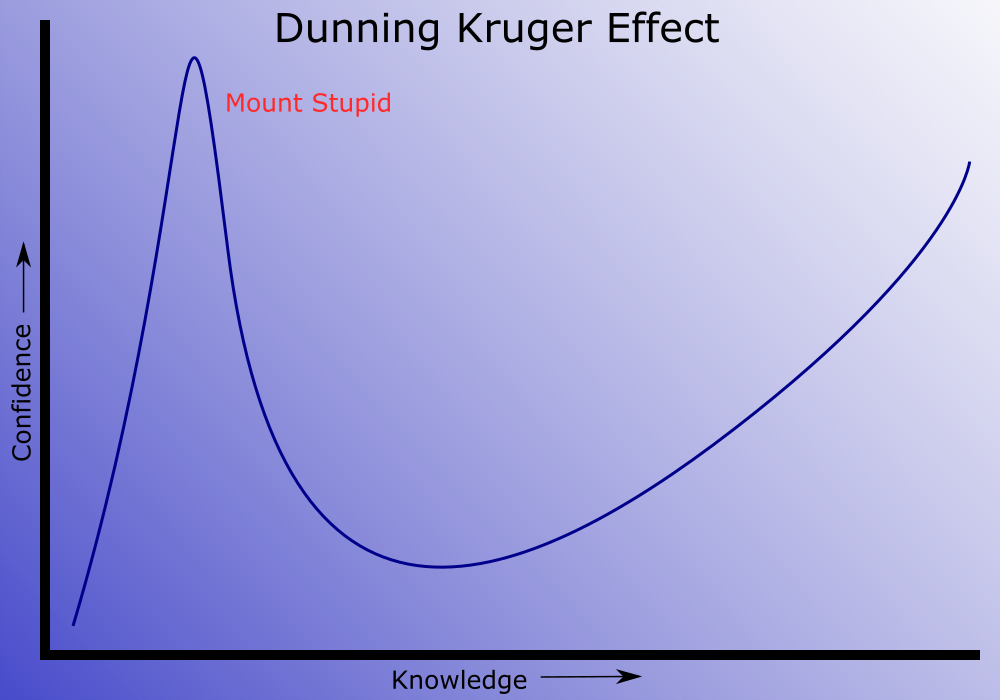

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a psychological phenomenon where people learn a little bit and then overestimate their ability. As someone starts to learn a topic their confidence rises quickly and out of proportion to their actual knowledge. They climb Mount Stupid. With luck they will pass over the crest and realize that they really don’t know all that much and start to learn in earnest.

The world of repair is full of the Dunning Kruger effect. Recently I have watched a lot of cringe-worthy YouTube videos where people confidently repair PCB’s, but to the real experts their efforts are horrifying! I don’t fault them for posting the video, but it is reckless for them to claim that they are experts in the topic. Unfortunately I think it is common for people to overestimate their ability to repair electronics.

So now let’s go over the various topics around RTR.

Progress

The march of progress has a lot to do with lack of repair-ability. We want things smaller, cheaper, and better. This has caused many circuits to be miniaturized to the point that special equipment and skills are required for soldering. It has forced us to move to flexible PCB’s that can be folded into tight spaces, and are almost impossible to rework. It causes cases to be assembled using specialized adhesives and ultrasonic welding that can’t be easily undone.

Products could be designed for easier repair, but you probably wouldn’t want them. Phones would be twice the volume, and less robust. Ultralight laptops would not exist. DSLR’s? Nope. And many things would be more expensive, if available at all.

Not every product would be affected in this way, but many of them would.

Profit

The end-goal of every company is to make money. Even charities will go away if they don’t at least break even. We cannot fault any company for that. Consumer electronics companies, however, are under extreme pressure to bring prices down and that is reflected in their low profit margins. In 2013, LG had a 0.4% net profit margin. Sony was at -0.9% (they lost money). Samsung was only at 13.3%. And Apple had a relatively large 21.7%. (source) John Deere’s net profit margin was only 7% in 2017. (source)

Adding even just a few percent cost to a product can have a huge impact on a company’s bottom line. Many of the “solutions” to RTR that I’ve read on the internet would add 5 to 50% to the cost of a product, or reduce other attractive features to the point that sales will be affected. From just an economic perspective, RTR cannot add cost without a corresponding change in what consumers are expecting to pay for the product.

Trade Secrets

There are a couple of ways that a company can protect their intellectual property. Patents are the obvious one, but trade secrets are the most common. Simply put, a trade secret is something that is not made public but if it were then the competition would benefit. Patents are expensive and not everything is patentable. Trade secrets are the most economical way to protect your IP.

Obvious types of trade secrets would be schematics, mechanical drawings, and source code. But not-so-obvious secrets could be the amount of torque on a screw, the order of manufacturing/assembly steps, and how firmware and security keys are loaded into memory.

In many cases, the information required for RTR is are trade secrets. It might be possible for companies to create new repair tools that do not release trade secrets, but that will increase costs due to additional development efforts and custom repair tools.

Counterfeit Products

Counterfeit products happen. A lot. I know of companies that have had their products counterfeited within a month or two of introduction. I’ve had my own products counterfeited, as have many of my associates. In some cases, the counterfeit products could outsell the genuine article by several times!

Often having firmware or some sort of security locked away inside of a micro-controller is the only thing preventing a PCB from being copied. Making the board repairable could also make counterfeiting possible— and many companies would understandably opt to not make the board at all if that were the case.

Access To Replacement Parts

To many it seems simple that a company could easily provide spare parts since they are already using them to build their products— but it is not that simple. Most companies outsource their manufacturing to another company. In the warehouse they might only have finished products, and none of the individual parts required to build the product! For that company to provide spare parts, they would need extra warehouse space to stock those parts, further increasing their costs and eroding profit margins.

To make matters worse, many companies don’t even have a warehouse. The contract manufacturer that builds their product can store some amount of product in their facility and then ship it direct to the distribution channels worldwide. The finished product might never enter a building owned by the main company.

But even if the warehousing issue is solved, there is the problem of sales, order tracking, and shipping of the spare parts. These spare parts will almost never be sold though the same sales channel as the original product. The manufacturer will probably have to sell the parts direct, requiring extra staff to take the order, fill the order, and ship it out. This is all a significant cost that will be passed on to the consumer one way or another. It could be built into the cost of the product, or the parts would be priced high enough to make it worth it. This doesn’t sound like a big deal until you get charged US$20 for a specialty resistor that cost them US$0.01 to buy— and the company still doesn’t break even on it.

Ability To Open It Up

Are some products beyond the ability for a customer to open up? Put a different way, should people be prevented from opening things up? For this section I am specifically referring to an individual customer and not an independent repair shop. I would argue that some products we should be able to open up, and other products should be buttoned up tight. What I can’t say is where that line between open and closed should be drawn.

Calibrated medical gear is something I wouldn’t want to see someone repair at home. Make a mistake with an X-ray machine and accidentally give someone an overdose of ionizing radiation? Nope. I would even be nervous about a TENS machine that you might have at home. Mess that up and who knows what would happen to you— but I can imagine an SNL skit about that!

On the other end of the spectrum are things that are obviously within the ability of someone at home. Guitar amplifiers, some PC’s, phone chargers, etc.

The line between open-able and closed is very nebulous, and probably defined by lawyers more than anyone else. Most desktop PC’s are open, but the dangerous high-voltages in the power supplies are isolated in their own metal frame. Cheaper devices like your home theater receiver can’t afford the extra cost so they go with an open-frame power supply that exposes the high voltages. How risk-adverse are their lawyers? If they are too adverse then they will probably do things to discourage people from opening up their gear.

Security Screws And Other Roadblocks

Some companies like Apple and Nintendo use custom screws to prevent people from opening up their gear. Other companies use adhesives, tamper evident stickers, or chassis intrusion sensors. None of these will prevent the truly motivated person from opening it up, so why are they there?

They are there to prevent the “casual repair guy” from getting in over their head. I’m talking about that uncle or grandfather that is always tinkering and think they can just pop it open and fix it. You know the type of person I am talking about. They usually say, “Hold my beer”, right before doing the deed.

There is also the kid (or possibly adult) that just likes to take things apart but lacks the ability to put them back together successfully. I was that kid way back then, and I ruined many devices in my day! Now we have YouTube, and you can find lots of funny and depressing videos of 10 year old kids taking apart their XBox— much to their parents displeasure.

So, security screws and the like should not be considered proof of a company trying to prevent you from repairing their gear. Only as proof of preventing 10 year old’s and your grandfather from “repairing” their gear. Tools to open these devices are available, but making them not so common just raises the bar for entry, literally.

Apple and the Intentional Slowdown

Batteries degrade over time. That’s just a fact of life, and physics/chemistry. They degrade in two ways: a decrease in overall charge capacity and a decrease in instantaneous current it can provide (independent of charge level). It is the instantaneous current that we are concerned with here.

Modern smartphone electronics are notorious for not consuming power smoothly. They will draw hardly any current and then all of a sudden draw a huge amount of power for a short period of time. This is a disaster waiting to happen when paired with a battery that can’t provide that large surge of power. The end result is a phone that crashes or suffers other seemingly random failures.

By reducing the speed of the phone Apple also reduces the peak power consumption to something below what the battery can reliably provide. What would you rather have: a phone that crashes all the time or a phone that is usable but slower? Slower, of course! Which is actually extending the usable life of the phone? Slower!

I find it interesting and also irritating that people are using this as an example of planned obsolescence, when it is exactly the opposite. Apple has done some crappy things, but this isn’t one of them.

I predict that slowing down electronics to deal with degraded batteries will become much more common in the future. Not just with iPhone, but Android phones and laptops too. Once the practice becomes more accepted, it will be done behind the scenes and without the user even knowing (except that things are slower).

Maintenance Contracts And Other Sources Of Revenue

Many companies make a living from selling the products and servicing them later. This is very common in the commercial markets for many kinds of machinery. The more specialized or temperamental the gear, the more likely there will be a service contract required. Most medium to large offices already have service contracts on their copiers, printers, and even some coffee makers.

For some applications, maintenance contracts are perfectly acceptable. Other applications, not so much.

The whole John Deere fiasco was a huge, unfortunate mess. For something that bad to happen, there isn’t one cause and it didn’t happen quickly. I’m not in that industry so I can’t comment accurately, but I will still hazard a guess…

This would have taken many years, possibly decades, to happen. John Deere got caught up in staying ahead of the competition, while getting more and more disconnected from their customers. At the same time the customers happily going along with it until one day they realize that they are doomed.

It is easy to blame John Deere for everything, and to be fair they should shoulder most of the blame. But tractors are expensive, some are several hundred thousand dollars. I have to wonder who buys an expensive and essential piece of gear for their company and they don’t look into maintenance and repair costs. The customer made a bad choice for not doing their research before committing to that product.

This mistake will eventually cost John Deere a lot. It’s possible it will cost them the whole company, but only time will tell.

Where Do We Draw The Line?

How far should we be able to repair something? Replace the whole product? Swap a module? Swap a PCB? Swap a component? Should we be able to fix one of the 5 billion transistors in a CPU?

I am intentionally be facetious, but it is an important question. The line we draw here is arbitrary. The line is different for different products. And the line is different depending on who is drawing it. There is no right answer, but there are a whole lot of wrong ones!

There is nothing that says we need to do component level repairs. Nothing that says we need to be able to replace phone screens and batteries. We only wish that repairs could be economical and timely. Maybe with some out of the box thinking, this problem could be solved a different way.

End Of Support

What happens when a company stops supporting a product? Should they open-source all of the design files? How long should they provide spare parts?

What if the company goes under? Should they establish something like a trust fund that keeps web servers going and pays another company to sell spare parts for them?

What if other manufacturers stop making the parts that this company uses in their products? This happens all the time. Sometimes the product is redesigned using a new part, or sometimes the product is discontinued. The semiconductor industry is weird. Sometimes chips are made for 20 years, and other times you’re lucky if they make them for 20 months.

Spare parts don’t last forever. Most electronic manufactures do not use parts older than 2 or 3 years. If they were to provide spare parts for 10+ years then they would have to roll over their stock every few years and other companies would have to be manufacturing fresh components.

All of this increases costs.

There is no good solution here.

Who Benefits?

Who would benefit from all of this RTR effort? In the case of tractors, a large percentage of customers would benefit. But what about Bluetooth Speakers? Would you repair one of those or just buy the latest thing? I would buy the latest thing. Probably.

We need to be careful with RTR laws. Different product categories benefit (or are harmed) differently by RTR laws. A single over-arching law might be nice but wouldn’t be appropriate. On the other hand, we wouldn’t want dozens of smaller laws since that would greatly complicate things.

We Couldn’t Cover It All

Before I wrap up this already long article, I want to give a quick nod to issues that I didn’t cover. There are lots of details to the John Deere mess. Examples of Apple trying to put third party repair shops out of business. The various RTR laws that are being debated.

I also didn’t really cover this from the perspective of the person doing the repairs.

What Can We Conclude?

We can conclude that the topic is very complex. Many products would either sacrifice features, raise costs, or cease to exist.

My personal opinion is that the consumer needs to drive the market. If consumers show they are willing to pay more for repairable products (and all the compromises that entails) then manufacturers will respond. But until company are sure there is a business opportunity there, nothing will happen.

Obviously this article doesn’t resolve any of these issues. My hope is that it helps educate people to some of the issues, and why RTR can be very difficult to implement.